Open Doc

Goals of the System

The goal of OpenDoc is to facilitate the easy construction of composable, customizable, collaborative, and cross-platform apps.

- Composable: apps should be able to be embedded within one another and integrate views from one application within another application.

- Customizable: apps should be able to be easily extended to support data and views from other applications. Users should be able to customize their application experience by drawing from components and data from a variety of applications.

- Collaborative: apps should shared documents across devices and allow multiple users to collaborate on a document in realtime.

- Cross-platform: apps should work across all devices and operating systems.

Ambitious!

According to GPT4's analysis, OpenDoc did not fully realize these goals:

Evaluating OpenDoc's performance against its goals:

- Composable (8/10): OpenDoc excelled in composability. Its architecture allowed for embedding and integrating components (or "parts") from various applications within a single document. This flexibility in combining functionalities from different sources was a core strength of OpenDoc.

- Customizable (7/10): OpenDoc offered significant customization capabilities. Users could tailor their documents by embedding diverse components. However, the extent of customization depended on the availability of suitable components and the user's technical skills. The ease of extending support for new data and views was more challenging and depended on the developers' engagement with the OpenDoc framework.

- Collaborative (4/10): While OpenDoc's component model supported the integration of various functionalities, it didn't inherently provide robust real-time collaboration or document sharing across devices. These capabilities would require additional technologies or custom development, which wasn't a primary focus of the OpenDoc architecture.

- Cross-platform (6/10): OpenDoc aimed to be cross-platform and made strides in this area, but achieving complete cross-platform functionality was challenging. The level of support and performance varied across different operating systems and platforms, and some intended capabilities were not fully realized due to the complexity of the task and the evolving tech landscape.

Overall, OpenDoc was quite strong in composability and customization, offering a unique and flexible approach to software integration. However, it was less effective in enabling real-time collaboration and achieving seamless cross-platform functionality, primarily due to technological limitations and the complexities of such integration.

How OpenDoc Worked

I use this taxonomy to think about the problems that OpenDoc would need to solve in order to accomplish it's stated goals:

- Persistence: storing the data in some format on some storage mechanism (files, db, memory, etc)

- Replication: replicating changes between devices, networking, etc

- Synchronization: handling simultaneous changes from multiple writers, resolving conflicts

- Identity: permissions, who can read and write to what data, who owns what, sharing

- Interoperability: allowing different apps to access the same data, representing data schemas

- Composability: creating views or components that can be reused across application contexts

- Extensibility: extending the set of views, components, and data

- Customization: enabling the end-user to customize their application runtime

- Cross-platform: run applications on many devices, operating systems, and platforms

In summary, OpenDoc focused on Persistence, Interoperability, Composability, and Extensibility.

Persistence

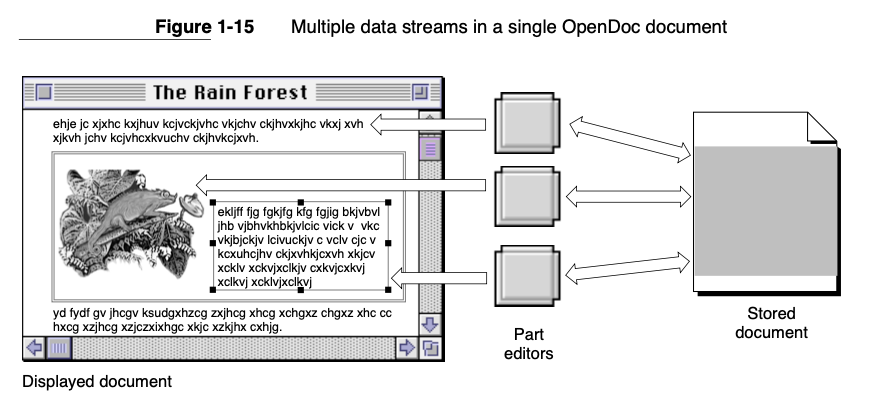

OpenDoc used a document-centric approach, where each document could store data from various components. It relied on storage formats like files, leveraging the file systems of the host OS. Classes in OpenDoc's API provided methods for saving and loading component states.

Being tied to the file system feels like a major limitation.

Replication

This wasn't a primary focus of OpenDoc; however, components could theoretically use external networking technologies for replicating changes across devices.

Synchronization

OpenDoc allowed multiple components to operate within the same document but didn't inherently manage synchronization of simultaneous changes. Conflict resolution and synchronization would require additional logic, possibly through custom component design or external libraries.

Identity

OpenDoc itself didn't handle permissions or ownership directly. Such functionality would be managed by the container applications or the underlying operating system.

Interoperability

OpenDoc excelled here, allowing different applications to access and edit the same data through a uniform interface. It used a standardized API for components, enabling them to be used across various applications.

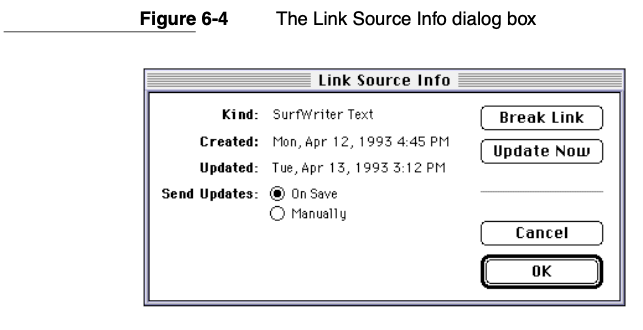

Wild to me that notification of updates wasn't part of the framework itself:

Making Content Changes Known

Whenever you make any significant change to your part’s content, whether it involves adding, deleting, moving, or otherwise modifying your intrinsic content or your embedded frames, you must make those changes known to OpenDoc and to all containing parts of your part.

- Call your draft’s

SetChangedFromPrevmethod. This call marks the draft as dirty, giving your part the opportunity to write itself to storage when the draft is closed.- Call the

ContentUpdatedmethod of each of your part’s display frames in which the change occurred, passing it an identifying update ID, obtained in one of three ways:

- returned from a call to the session object’s

UniqueUpdateIDmethod (if the content change originated in your part’s intrinsic content)- propagated from a link destination (see “Link Update ID” on page 375)

- propagated from a call to your

EmbeddedFrameUpdatedmethod (see “The EmbeddedFrameUpdated Method of Your Part Editor” on page 381)

CallingContentUpdatednotifies your containing parts—and their containing parts, and so on—that your content has changed. The notification is necessary to allow all containing parts to update any link sources that they maintain.You should call these methods as soon as is appropriate after making any content changes. You may not have to make the calls immediately after every minor change; it may be more efficient to wait for a pause in user input, for example, or until the active frame changes.

Composability

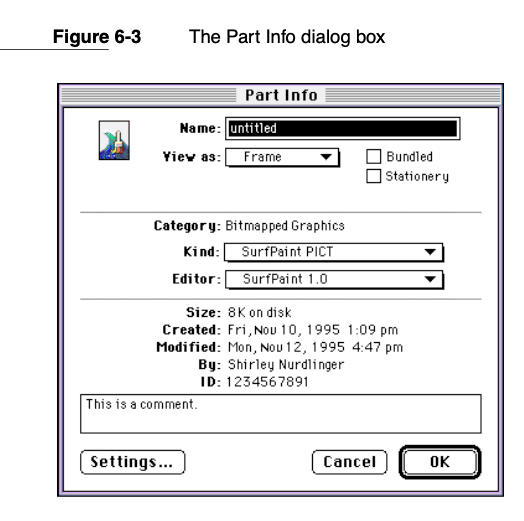

OpenDoc's architecture was highly compositional, enabling developers to create reusable components (or "parts") that could be embedded across different OpenDoc container applications.

Extensibility

OpenDoc allowed developers to extend the functionality of applications by developing new components or modifying existing ones, enhancing the capabilities of container applications.

Customization

End-user customization was achievable through the use of various components. Users could tailor their experience by choosing which components to embed in their documents.

Cross-platform

OpenDoc aimed to be cross-platform, functioning on different operating systems. However, achieving seamless cross-platform functionality was complex and depended on the compatibility and support of the underlying OS and hardware.

The OpenDoc Human Interface Guidelines

Frames, facets, and embedding

Transclusion / Links

Copy/paste and drag and drop were a primary means of moving data between applications. When an item was dropped or pasted, the receiving part decides what to do.

The destination part, when it receives transferred data, decides whether to accept it or not, and whether to incorporate the data into its intrinsic content, or whether to embed it as a separate part. Users can override the destination part’s default decision by using the Paste As command.

Transclusion in OpenDoc feels too complicated.

Why OpenDoc Failed

Personal Theories

To centered on documents, desktop publishing, printing, and metaphors peculiar to the time.

Other thoughts

Unless you have application groups who want to create functionality to run on your OS, it’s one hundred times harder to figure out what you’re supposed to be doing with your OS. Without those application groups telling us they needed–or didn’t need–OpenDoc, we were flying blind. (Witness the pathetic track record of other Mac OS technologies at the time to realize just how dead-on the phrase “flying blind” is: Copland, QuickDraw GX, QuickDraw 3D, Apple Guide, PowerTalk, CyberDog. All abject failures, despite their technical prowess.) This isn’t a problem that exists at Microsoft (at least, it certainly isn’t evident.) The Office group needed a component architecture, so they wrote one. They needed it integrated into the OS to support things like Publish/Subscribe, etc., and to leverage it into Explorer…it happened. The OS gets exactly the technology it needs because the application groups know exactly what they want. No one has to guess.

If you got OpenDoc and the possibilities, you loved it. But getting it meant thinking a certain way, wanting to precisely tailor something to your own specific needs. And it's no surprise that an all-in power user took to it, while the average user might just have shrugged and went on with their current apps.

Demos

So, you've got here a Cyberdog web browser being opened up by Macromedia Shockwave for FreeHand running inside of our Netscape plugin part, all inside of ClarisWorks, again completely seamless to the user, and all through OpenDoc. ClarisWorks didn't have to support anything but the OpenDoc API; they get all this for free.